Small Listening is Big - the paradox of growing big as we listen to small

Owls help me remember to listen to the still and small.

If I sit very still, no footsteps, no rustling paper, no pen across the page, no warm air blowing from the furnace, not even my breath or tucking hair behind my ear, I can hear a pair of owls hooting in the dawn. It is a moment of awe, joy and resilience. They are calling to one another about nesting, lands, and family.

With our loud, fast world and the clamor of voices speaking over one another to get my attention, I wonder how many mornings have I have missed the owl cries of home and love?

Hearing the owls outside my window has trained my ear to listen for God’s small, still voice, the one of home and love. At first, I had to lean in to hear God’s beautiful voice over the noise of the world - over the shouting, name-calling, power-tripping, deal-making, truth-twisting, image-preening chaos, over my own insecurities and fears. But the longer I practice this delicate listening, the more I understand it is a listening underneath the strife and strike rather than over the top. It is listening low and small and spacious.

It is attuning to what poet Annie Lighthart calls the second music.

The Second Music by Annie Lighthart

Now I understand that there are two melodies playing,

one below the other, one easier to hear, the other

lower, steady, perhaps more faithful for being less heard

yet always present.

When all other things seem lively and real,

this one fades. Yet the notes of it

touch as gently as fingertips, as the sound

of the names laid over each child at birth.

I want to stay in that music without striving or cover.

If the truth of our lives is what it is playing,

the telling is so soft

that this mortal time, this irrevocable change,

becomes beautiful. I stop and stop again

to hear the second music.

I hear the children in the yard, a train, then birds.

All this is in it and will be gone. I set my ear to it as I would to a heart.

What to call this second music? You might call this the music of the spheres, a kind of song reverberating in the cosmos. But who is singing it? I tend to think of the second music as God’s own singing voice that he sings from the Trinity community. The song has notes of life, truth, beauty and goodness, that once heard create more of the same. Whatever you call it, it deserves our rapt attention. But as it has competing voices that are often louder and more urgent, we often only gets fuzzy hints of the beautiful song.

Writer and poet Maggie Smith describes our challenge this way,

Life’s everyday activities create static - a constant hum of responsibility, news, reminders, encounters - and our work is to dial past that static to hear the quiet voice inside us.

Maggie Smith

We might have grown accustomed to life coming at us loud and fast with big effects. Our culture, rarely if ever, whispers. The 24-hour news cycle doesn’t speak quietly or small. Not politics either. Even our churches rarely quiet down and get small enough to listen deeply. And our minds race with things to do and places to be. In our effort to make a difference, to count for good, we often look only for the big ways and miss the small ones.

The call of God’s still, small voice is a pattern found throughout Scripture. In Psalm 46, God says – Be still and know that I am God. The boy Samuel woke to God’s subtle voice in the night in the sanctuary. (1 Samuel 3) The prophet Elijah heard it when feeling so alone in following and acting for God, he ran away and feel asleep in a cave. God graciously came to him , asking, “What are you doing here, Elijah?”.

When Elijah’s answered, “I’ve been working my heart out”, God invited him to stand still in God’s presence as God moved near him. What happened next seemed to surprise Elijah. First, a violent wind shattered the mountain, but God was not in the destructive wind. Then an earthquake rattled the land, but God was not in the rumbling quake. Next a fire burned the terrain, but God was not in that fiery destruction either. Not until a still, small voice came to Elijah, was it God’s voice. (1 Kings 19)

Like Elijah, we may know how to run and work and expect God to speak in mighty ways. But. . . .

How might our racing around and frenetically working keeping us from hearing God?

In what ways are we listening for God to speak only in mighty and splashy ways?

How can we let God speak quietly, tenderly, and non-competitively and actually hear him?

Perhaps God was enlarging Elijah’s capacity to hear God’s quieter ways by introducing his small voice – a paradox worth considering. Small usually refers to quantity, capacity, or power. But it can also mean young, poor, or humble. God’s still, small voice comes from a Hebrew phrase kol demama daka which means the “sound of a slender silence”. It carries with it a fullness of listening, hearing, heeding and responding. Before we think generous listening is without action, God’s still, small voice speaks with an invitation to act.

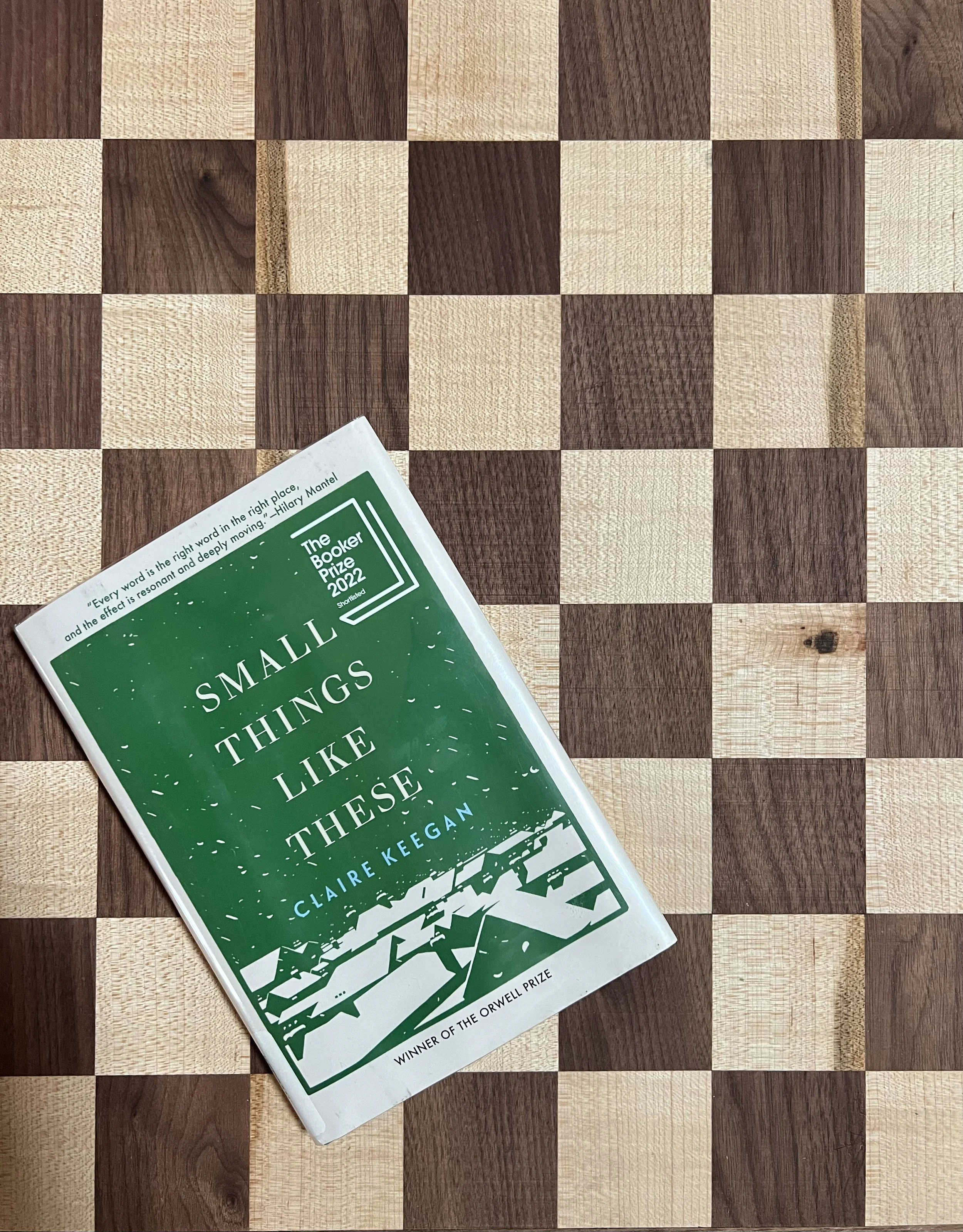

I read a library book recently that took my breath away. I read it in an afternoon and promptly bought my own copy. Then, I discovered the excellent movie of the same name starring Cillian Murphy. As I read this slender book, I realized my body had had gotten quiet, still, and small. I was hearing those morning owls. I was hearing that second music.

The book is “Small Things Like These” by Claire Keegan.

Bill Furlough is an Irish coal man. He is a laborer working from dark to dark to support his family and keep his five girls in the local Catholic school. He owns the fuel business but chooses to do many of the deliveries himself and in doing so, he stands on many doorsteps. He sees his small river town from front and back.

Bill is a looker.

He sees the surfaces of things and below. He sees hidden things, dark things, small things and big things. On his rounds, he cannot help what he sees – a boy drinking milk from the cat’s dish behind the priest’s house, another boy picking up twigs far from town, and young girls working in the convent laundry where clothes are washed and pressed spotless and smooth. Bill comes home every day dirty and exhausted and washes up in a sink just inside his front door. At night, he talks about these small things he sees with his wife. They can’t be helped she says.

All the while, Angelus bells ring clear and bright three times a day calling the town to pause and remember Christ’s incarnation. At the noon bells every day, Bill and his employees pause to share a hot meal.

In the end, Bill pushes aside shame and the status quo to do a kind and local thing, one of the small things that couldn’t be helped. One of the small things that will likely cost him something big. It is an act of generosity in the face of greed, an act of love among hate and indifference, an act of freedom in the face of imprisonment.

As he walks through town with a barefoot child, Bill asks himself,

Was there any point in being alive without helping one another? Was it possible to carry on along through all the years, the decades, through an entire life, without once being brave enough to go against what was there and yet call yourself a Christian, and face yourself in the mirror?

How light and tall he almost felt walking along with this girl at his side and some fresh, new, un-reconisable joy in his heart. Was it possible that the best bit of him was shining forth, and surfacing?

Some part of him, whatever it could be called – was there any name for it? – was going wild, he knew.

The fact was he knew that he would pay for it but never once in his whole and unremarkable life had he known a happiness akin to this, not even when his infant girls were first placed in his arms and he had heard their healthy, obstinate cries.

Bill Furlough

I notice he is trying to name that part of him that was going wild. Is there any name for it? And Furlough’s questions are still ringing in my heart.

If we are willing to still ourselves in God’s generous presence, in his beloved son, Jesus, and risk what we hear, then we might become more than veneer Christians. We will be listening not for windstorms, earthquakes or fires. We will be listening to God’s beautiful whisper where small is tender, humble, and spacious, so spacious it becomes big, generous, life-giving. We will be listening for the second music. And we might become actual Jesus’ followers.

Bill continues his reflections back into his childhood,

He thought of Mrs. Wilson, of her daily kindnesses of how she had corrected and encouraged him, of the small things she had said and done and had refused to do and say and what she must have known, the things which, when added up, amounted to a life.

It may not be explicit, but as Bill remembers Mrs. Wilson from his childhood, he feels the result of her listening, truly listening, to the genuine call of those Angelus bells. And after hearing the rivals of God’s whisper which are loud and certain, Bill hears Love’s still, small voice growing clearer as he listens. And he acts.

As we attune to God’s presence ringing in our interior landscape (it already is), we will hear his whisper in the background at first and wonder if it isn’t simply our own self speaking. It takes some tuning. That is how it is - like tuning to a radio channel to hear a song. (Remember knobs?)

But if we keep listening and tuning to goodness, beauty and truth, while it may not get louder, God’s voice and character will come forward in us. Only then do we come alive and find deep happiness.

Only the slender silence of a loving God is capable of slicing between bone and marrow, through the noise of the street, into fear to find courage. Only God’s gentle whisper in Christ can tell us who we truly are and call us from his goodness to act kindly in a mean world.